review of *Frankie and Johnny in the Clair de Lune*

performed at Interplayers Professional Theater through Oct. 3

An apartment. Very dim light. Loud, guttural yelps of orgasmic delight. Laughter. "I wish I still smoked," she says.

Well, they're certainly having a good time tonight.

Too bad the mood isn't maintained in Interplayers' production of Frankie and Johnny in the Clair de Lune (through Oct. 3).

The problem's in the acting. For most of the first act, line-deliveries didn't match emotions described in the script; beats were lost, significant moments rushed through and undervalued.

As Johnny -- the short-order cook who's lonely and curious, but determined to improve his emotional lot in life -- John Henry Whitaker portrays a motormouth who doesn't speak quickly. He's a passionate guy who displays no passion.

Whitaker doesn't enact lines, he recites them. He's supposed to stare at Frankie (Karen Kalensky) intently and doesn't; he's supposed to be playful (during a close-your-eyes-and-sit-on-the-floor game) and isn't. Later, when he's supposed to express shock at witnessing an act of violence over in another apartment, he's about as surprised as when you find something that was supposed to be filed under M filed instead under N.

A carpe diem outburst, delivered while kneeling, seems more creepy than full of any lust for life. The "open your robe" sequence -- Johnny just wants to admire her naked body, just for 15 seconds -- doesn't work as well as in the movie, in which Al Pacino expresses puppy-dog appreciation while Michelle Pfeiffer chatters about this and that, nervously. Here it's more like a gynecological examination with an irritated patient.

Kalensky's character, meanwhile, is insecure and lacking in self-confidence: She's not so sure she wants this fancy-talkin' fella making goo-goo eyes at her, coming on way too strong. But Kalensky's manner is more festive (let's party!) and frantic (who is this guy who I've invited into my bedroom?!) than insecure. Again and again, she pulls her robe around herself, indicating her defensiveness. But Frankie's tattered self-esteem doesn't become evident until much later, and by then it's too late.

For much of the second act, Frankie and Johnny (played in this production by real-life spouses) act like a long-married couple, negotiating just how much they can tolerate in the other. They've lost out on their dreams; they have plenty of regrets; they're feeling older.

Director Jonn Jorgensen doesn't coax much passion out of Whitaker. In a couple of moments calling for tenderness and physical intimacy, Jorgensen has Whitaker planted over by the kitchen counter, all the way across the stage from Kalensky. (A promise never to hit a woman is more credible if you're actually within range of hitting her when you say it.)

The first-act misinterpretations are unfortunate, because Terrence McNally's script has many good observations and touching moments, and because the acting becomes simpler and more heartfelt in both of the hopeful act-ending sequences.

Kalensky has a wonderful monologue when Frankie recalls her high school prom -- illuminated by the sunrise just outside her window, her face glows with pleasing nostalgia.

And Kalensky doesn't make a big deal of Frankie's having the munchies: Her literal hunger implies her emotional hunger and loneliness, but Kalensky suggests the point simply, without indicating her character's neediness.

A lovely final sequence, rendered simply both in the acting and the directing, has Frankie and Johnny bathed in soft light and Debussy's music, yet with the romance undercut -- realistically, amusingly -- by some playful bickering.

So the evening's not a total loss. But McNally's script is much better than the performance it's receiving here.

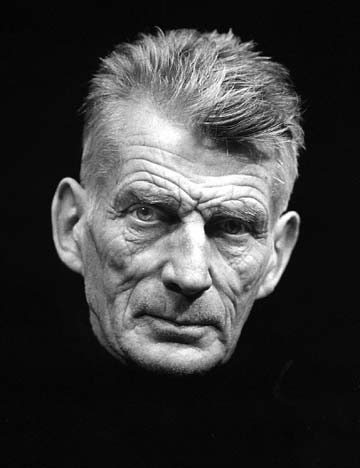

[photos: playwright Terrence McNally, from the La Jolla Playhouse; Kalensky and Whitaker watching TV, from the Interplayers production; by Young Kwak]

Labels: Frankie and Johnny in the Clair de Lune, Interplayers Professional Theatre, John Henry Whitaker, Jonn Jorgensen, Karen Kalensky